In a previous post, we discussed the influence of “primitivism” on Western art. We determined that a “primitive” artist is one that is “untrained” as opposed to a trained Western artist. An important fact that we mentioned was that, even though the artists were “primitive,” the Western artist gleaned from and were heavily influenced by them.

This raises questions of whether one can or should leave one’s mind uncontaminated by art theory in order to produce art. Here we discover that it may be possible that one can inhibit spontaneous creation through the limitations of theory. However, even though it can become a barrier between the artist and creativity, theory is often a necessity to understand and interpret the world at a deeper level.

Trained artists may put forward the idea that it would be near impossible to create art without theory. However, the idea of producing art spontaneously, with a mind uncontaminated by theory is possible. It is especially true for the “untrained” artist. They have shown this as a possibility, as we have seen over the centuries of art making.

An “untrained” artist is one who has had no formal instruction in the discipline of fine art; that is, one whose work would be uncontaminated by art theory. We find a slight contradiction here, though. As Berger puts forward, the “untrained” artist has in one form or another been “contaminated.”

These artists are often driven by their culture, politics, philosophy, linguistics, anthropology, psychoanalysis, and sociology, which influenced their “thinking” and “doing” (Berger, 1977). Even though there is no formal training, some form of “training” of the mind does occur.

One can then reason that, whether trained or untrained, art does not occur in a vacuum. It is therefore necessary to keep this in mind when we look at what untrained artists have and can accomplish. We can take valuable lessons from the untrained works of an untrained artist. We have such an example in the well-known South African and international artist Willie Bester.

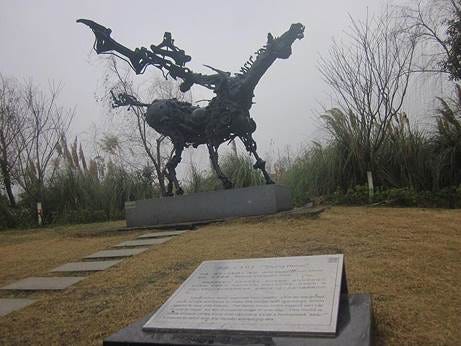

His work documented political statements about the injustices of Apartheid South Africa, as well as post-apartheid actions and activities. Below is an example of one of his dynamic works. This one represents the rapid advancement of the current era. This sculpture reflects discarded tools and parts that represent the rapid advancement of the current era (as per the inscription next to the sculpture).

Even though Bester was emersed in art from a young age, he found it necessary to attend art classes to increase his creative ability. In his case, the foraging into art theory did not stifle his creativity; instead, it gave him a renewed vigor as his latest works indicate. The works retain their iconic execution as he reflects the human condition in a solo exhibition at The Koena Art Institute (ended July 31, 2025).

One of the stark realities of this “dilemma” (theory or no theory) is that each work of art comes with a context. We mentioned some of these examples at the beginning, which include, for example, psychoanalysis. Under Freud’s teachings, we discover that we often run our lives in the “unconscious,” that is, we do things without a conscious process (Freud, n.d.).

When we create art, therefore, the “unconscious” is often the driver. The daily “unconscious” intake of information allows the art to be expressed visually—that is, in the words of Barber, “using visual symbols to explore feeling and emotion” (Barber, n.d.).

Another aspect of the influence of the “unconscious” is that many artists cannot explain elements in their work. As an artist, though, you do not have to explain everything, as the viewers also run the visual through their own “looking” experience.

This experience creates the scenario of “An artwork may have a particular meaning or significance for the artist, but when it leaves the studio, it becomes a public object” (Carter, 1990). Thus, the interpretation of its content and context may be different for each viewer.

The interpretation of art does not require theory, and the same applies to the making of art. We have established that the “untrained” artist has as much of an impact as that of a trained artist. However, as we noted in a previous post, the works of untrained artists influenced the trained artists quite heavily. The example of Willie Bester has also emphasized the “training” that could enhance and increase creativity.

One could therefore conclude that, for some, theory may be a vital formula for expressing feelings and emotions. For others, though, it might stifle their freedom of expression and steer the work into an “artificially induced” product. Thus, it is up to the individual to decide whether theory is essential to create art or whether it is an unnecessary venture.

References:

Barber, V. (n.d.). Art Therapy. Astonishmepress. Retrieved August 5, 2025, from http://www.astonishmepress.co.uk/art/arttherapy/index.html

Berger, J. (1977). Ways of Seeing. British Broadcasting Corporation.

Carter, M. (1990). Framing Art: Introducing Theory and the Visual Image. Hale & Iremonger.

Freud, S. (n.d.). Untitled. Troy University Spectrum. Retrieved August 5, 2025, from https://spectrum.troy.edu/kness/Freud%20Handouts/The%20Structure%20of%20the%20Unconscious.pdf

Image:

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d7/Willie_Bester_-_Flying_Horse.jpg/960px-Willie_Bester_-_Flying_Horse.jpg

Again a tour de force in educating the 'untrained', that's me. Greatful for the growing understanding. Good piece, contemporary and relevant.